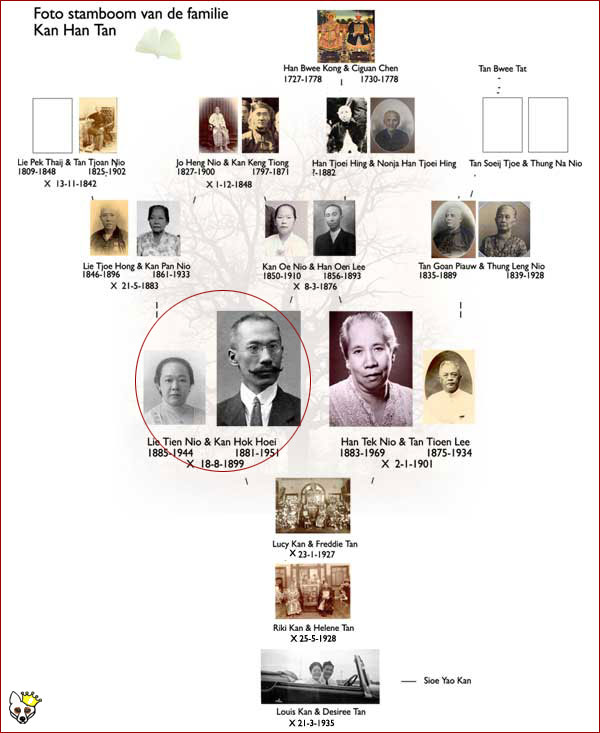

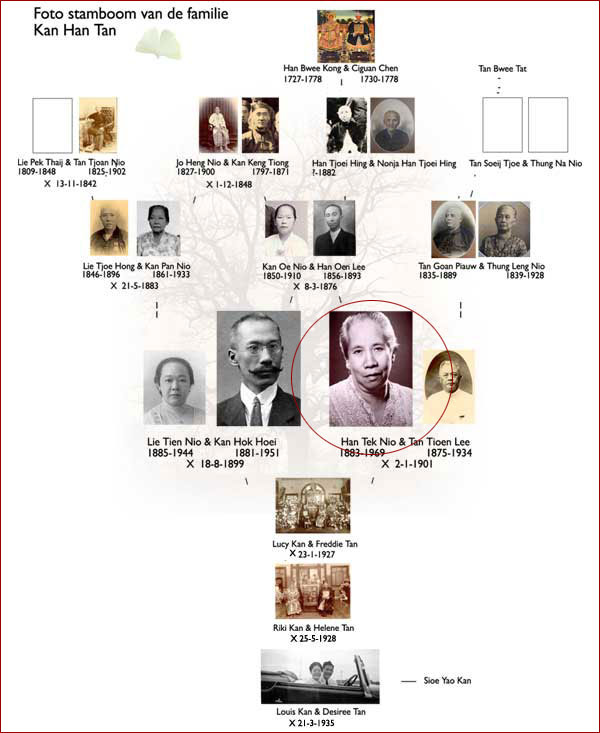

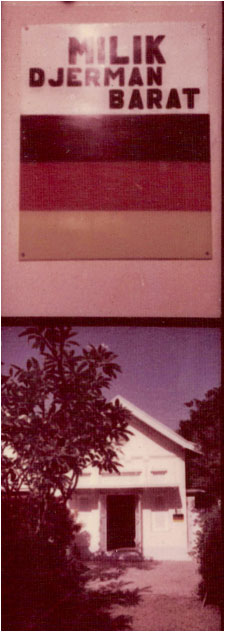

03. H.H. Kan’s last home: Djalan Teuku Umar 15, Djakarta |

|||

|

|

|||

Introduction |

|||

The idea for this story came during an interview in the context of the Oral History Project of the CIHC. The interviewer asked me about my earliest memories that I can recall. To my own surprise I could remember vividly the violent usurpation and occupation of my grandfather’s house by the Pakistani. I even can see the whole event as a 3D movie in clear details. Another reason to write this story is to kill the myth of the wealth of my grandfather at the moment he died. |

|||

Djakarta, Djalan Teuku Umar 15 the last home of H.H.Kan |

|||

|

From the multi-lingual description under the house number ‘15’ in this photo, it is clear that this house is used as the Pakistani Embassy. My grandfather H.H. Kan, a former Volksraadlid, lived in this house after World War II until his death in 1951. It was also the last house that he could call his own. When he died, his body was laid out in an open coffin in the house’s front porch. This front porch is an open space seen on the photo as the protruding part of the house on the right. Through that porch, one can enter the house through the front door. |

||

The ancestral altar stands in the first room behind the front door. On the day of my grandfather’s death, incense was lit during the burial and coffin preparation ceremonies. The door connecting the front porch and the room where the ancestral altar stands was left open in order to connect the coffin to the altar. The coffin was placed as close as possible to the altar, and thus right near the door. Apparently the word had spread that the front door was open, because without warning a group of Pakistani forcefully entered the house and occupied it. In the process, the Pakistani had to walk past the coffin with their luggage: suitcases and boxes. This disturbed my father, who was busy with preparations for the burial ceremony at the coffin. |

|||

|

The Pakistani even tried to occupy the pavilion in which my aunt Lucy, my grandfather’s eldest daughter, lived. This did not work, thanks to the fact that she was married to a German national. Later on, they had put a sign in front of the pavilion saying “Property of the West German Republic.” This plate was later supplemented with translations in German and English: “Bundesrepublik Deutsland” and “West Germany” The few pieces of furniture and belongings of my grandfather’s, which had been retrieved from his confiscated house in ‘Parapatan’, were dumped by the Pakistani in the front garden and on the street. Thus, many objects were lost such as photographs, important documents, family data and other personal things .Before World War II, my grandfather owned three villas: the house on Parapatan, a country house for his wife in Tjitjoeroeg, and Villa Mei Ling in Bandung. The latter was meant to be a museum of the Kan-Han family. The villa was filled with art and antiques. |

||

|

|||

EpilogueThis story demonstrates some aspects of the community in Indonesia: 1. My grandfather H.H. Kan had during the Dutch East Indies government as a member of the Volksraad some (political) influence. During the Republik Indonesia time of president Soekarno this influence was reduced to zero. The fact that the police refused to chase away the Pakistani from the home of H.H. Kan demonstrated the lawless condition of the Chinese in Indonesia. This was clearly visible during the “bersiap time” but also during the pogroms in the years thereafter such as in 1960 and 1963, but more explicitly during the genocides of 1965-1967 and in 1998. 2.My grandfather had called over the hate of the nationalistic Indonesians by voting against the Soetardjo petition.

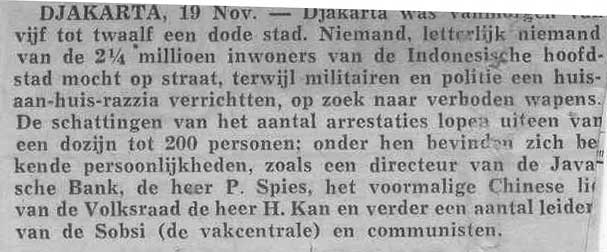

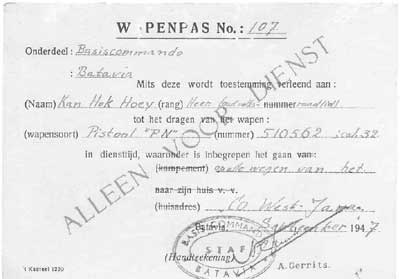

This resulted in several bullying events after the sovereignty transfer in 1949. The last one just before he died, namely he was put in jail due to owning a gun illegally.

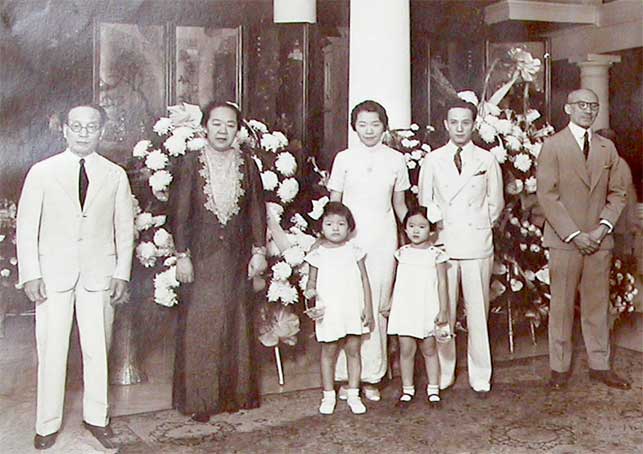

3.He had an official gun permit issued by the Dutch East Indies government but not one by the Indonesian government. According to my father, my grandfather came out of jail in a bad condition and ill and as a direct result he died shortly after. This incident was even reported in the Dutch newspapers, resulting in several letters of concern. So my father received a letter from his former cello teacher Charles van Isterdael. On the wedding photo of aunt Hilda, daughter of H.H. Kan (far right) and Lie Tien Nio (in dark dress) with Jesse Sung, the son of the Chinese consul in the Dutch East Indies in 1934, one can see the immense proportion of this screen.

During the night in which my grandfather was arrested by the Japanese, my grandmother had a dream that this screen tumbled down. This night can be exactly traced due to a diary of the journalist Nio Joe Lan (Dalam Tawanan Djepang, 2nd print 2008, page 20) namely the night between April the 26 and 27 1942. After WO II the screen disappeared. The Pakistani never payed any rent. Even worse: during my father’s stay in the Netherlands between 1954 and 1957 they even managed to receive a cadaster paper stating them as the main resident of Dj. Teuku Umar 15. With this paper they tried to remove my aunt Lucy from the pavilion. So the German embassy put a plate “Milik Djerman Barat” (property of the republic West Germany) in front of the building. During my school time I still suffered from the anger about the vote against the Soetadjo petition by my grandfather. The history teacher told my class “His grandfather was a traitor of the country where he was born just to please the Dutch occupier”. Due to this infame of my grandfather our family was called Blandist and suffered additional discrimination. This was especially dangerous during the New Guinea crises at its summit. |

|||

|

Sioe Yao Kan. Berkel, last updated May 2018 |

|||